CQ5: Creativity is thinking outside the box. But which box?

Step 1: Origin of the phrase: The Nine-dot puzzle

The oldest record I can find on the puzzle I found through google and that record shows that the puzzle was already mentioned in 1914 in Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles Tricks and Conundrums.

The oldest record I can find on the puzzle I found through google and that record shows that the puzzle was already mentioned in 1914 in Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of 5000 Puzzles Tricks and Conundrums.Step 2: Problem-solving research with the Nine-dot puzzle

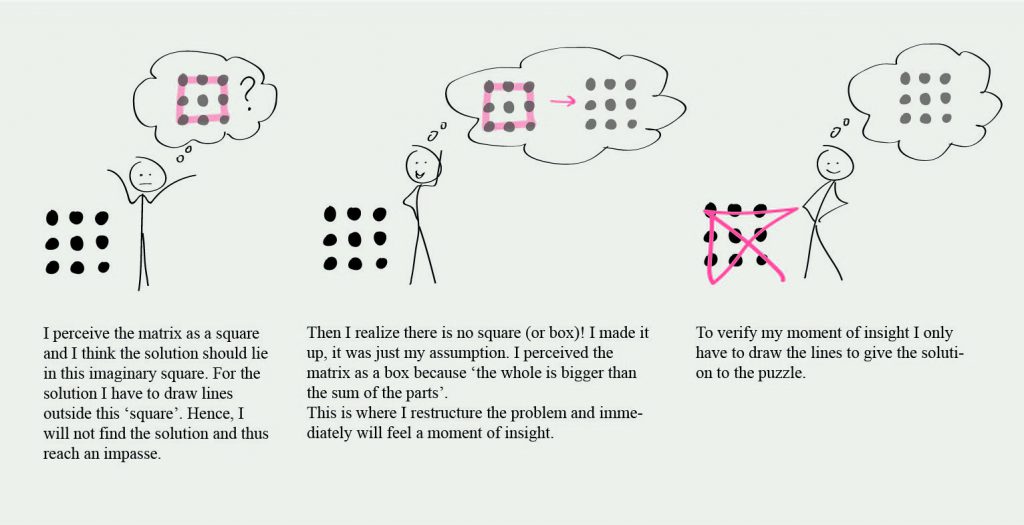

- First, you reach a so-called impasse. It is a period of no progress. Maybe this is the moment when you realize you have a problem that you cannot solve with the methods you are using.

- Second, you have to restructure the problem. You probably no the phrase ‘looking differently at the same thing’. That is restructuring the problem. Remember the Gestalt theory is all about how you perceive ‘things’. You need to change your perception of the problem.

- Third, when you have restructured the problem, the solution will ‘come to you’ suddenly. This is the moment of insight. The famous Eureka-feeling the Aha-Erlebnis. You know what I mean.

Step two and step three happen almost at the same time. Restructuring leads directly to ‘seeing the solution’.

Solving the Nine-dot puzzle is a perfect way to test this theory. See picture below.

Step 3. Problem-solving in relation to creativity

We now understand the origin of the term outside-the-box thinking, and how it founds its way into psychology. What we miss is the relationship between problem-solving and creativity. The Gestalt theory on problem-solving is used as a theoretic framework for research on creativity. I will explain more about the Gestalt theory in chapter 2, many of our assumptions on creativity have its foundations in that theory so it is definitely worth looking into. But you are going to have to wait :).

Back to the box.

What is the box?

What often happens is that we use the imaginary square from the Nine-dot puzzle as a metaphor for the boundary of a problem. But remember, the square is not real and is no part of the criteria for the solution. Again, there is no box! It is your own assumption or imagination that made it part of the problem. And if we say the box is the boundary of the problem, we act as if the nine-dots form an actual square. I think this is what happens often in reality, but it is, in fact, a wrong interpretation of the box. And it has consequences.

If we use this metaphor as a way to solve problems, we think we need to relax goal constraints to go outside the box:

‘How can we come up with our newest innovation?

‘We have to think outside the box.’

‘Oh OK, so everything is possible, let’s come with some crazy ideas or, let’s move away from the problem.’

See my point?

I’m not saying that you cannot challenge the criteria. I’m just saying that you need to be aware that if you use outside the box thinking in this way, that this is exactly what you mean. And, my assumption is that when a boss tells his employees to think outside the box, s/he is not asking for them to challenge the criteria s/he gave them. Although I would encourage them to do just that.

Fortunately, more experienced creativity professionals will probably not fall into this trap. They will use the meaning the Gestalt psychologists used, in my words:

The box is not the boundary of the problem, the box is the boundary of your imaginative thinking!

Your box is how you see reality with all your perceptions and assumptions. To solve a problem, you need to question your assumptions. A more relevant question would then be:

‘What is ‘the box’ of our problem? Hence, what are our assumptions?’

In Gestalt-terms this is what we call ‘restructuring the problem’ as I explained at the beginning of the article. This next issue we need to tackle is the belief that this restructuring of the problem leads to a solution, in other words, leads to creativity.

Does outside the box thinking lead to creativity and thus a solution?

The restructuring will lead to the moment of insight and thus to a solution, that is what the Gestalt psychologists theorized. However, it turns out that ‘looking differently at the same thing’ does not equal creativity, and it will not lead to a solution per se. Hence, the actual Gestalt-meaning of the phrase outside the box is not always true. Research shows that outside the box thinking does not lead to creativity, per se.

In 1981 Alba and Weisberg conducted interesting to research in this matter. In their experiment, they literally told the participants that the had to draw lines outside the imaginary square to get the solution, at the beginning of the assignment. They hypothesized that the hint would lead to restructuring and thus a great number of participants would solve the problem. However, the ‘go outside’ hint was not effective. Even though most participants drew lines outside the imaginary square, only 25% of the participants solved the problem. And that was not significantly more than the participants that did not get the hint (Weisberg, 2006). Other research shows the same type of result: Lung and Dominowski (1985), MacGregor Ormerod and Chronicle (2001).

Even though we might believe that outside the box thinking is a great way to describe creativity, research concludes differently. But maybe we can fix this.

What if we look at ill-defined problems?

The conclusion I drew two sentences ago might be false for ill-defined problems. As argued above we can conclude that restructuring problems do not lead to insight per se. However, what we are forgetting is the type of problem involved. You see, Gestalt psychologist used so-called ‘insight problems’ for their research. These problems are characterized as follows:

One, the problem requires restructuring.

Two, all variables are known.

Three, the problem has one solution.

Hence, we are talking about well-defined problems. However, how many times you have to solve well-defined problems? Almost never. Most problems in work and private life are ill-defined. You don’t know all the variables, context is everchanging, there are multiple solutions to the problem.

It might be true that restructuring well-defined problems does not lead to insight. However, we do not know for sure if restructuring ill-defined problems don’t lead to insight. At least I am not aware of any research on this matter. From my experience though, I would say that restructuring ill-defined problems is, in fact, the key to insight.

Outside the box thinking is key for solving ill-defined problems

If I use the Gestalt-meaning of outside the box thinking (changing my perception of the problem, challenging the existence of the box), I think outside the box thinking is the only way towards creativity when it comes to ill-defined problems.

All creativity (in this context creativity=solving problems) starts with understanding the problem. The real problem. In the start-up world there is a phrase: ‘Assumption is the mother of all f*ck ups’. This is not only true in the start-up world but in life in general. That is why we need to observe and listen without judgement and with curiosity and act like Leonardo da Vinci in that matter.

I wish scientists would use ill-defined problems to investigate the issue of restructuring. Seems like a topic worthwhile to me.

Conclusions

Firstly, outside the box thinking in terms of moving away from the problem is nonsense but is, unfortunately, a commonly made mistake. Google ‘training creative thinking and outside the box’, and find out how often you run into this interpretation of outside the box. I was a bit shocked…

Secondly, outside the box thinking, in terms of restructuring the problem (as the meaning was intended by Gestalt psychologists), does not lead to creativity per se, for well-defined problems.

Thirdly, we don’t know if outside the box thinking in terms of restructuring the problem (as the meaning was intended by Gestalt psychologists), leads to creativity, for ill-defined problems. I think it does.

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ21: How do people solve problems?

The Cognitive Analytical Model (CAM) is described by Robert W. Weisberg in his 2006 book: Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Sci

CQ8: Divine inspiration

Inspiration is a Gift from the Gods. Right. Let’s start our historical review with the Big 3: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. I will shortly mention t

CQ14: What is Creativity?

Understanding how people create has been a serious topic for philosophy since the Renaissance (CQ9). But when Guilford acknowledges creativity to be a

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.