CQ14: What is Creativity?

Understanding how people create has been a serious topic for philosophy since the Renaissance (CQ9). But when Guilford acknowledges creativity to be a valid topic to research in psychology, a definition of the word ‘creativity’ became more urgent.

What defines creativity?

Guilford wrote:

‘creativity refers to the abilities that are most characteristic of creative people’ (Guilford, 1950: p444).

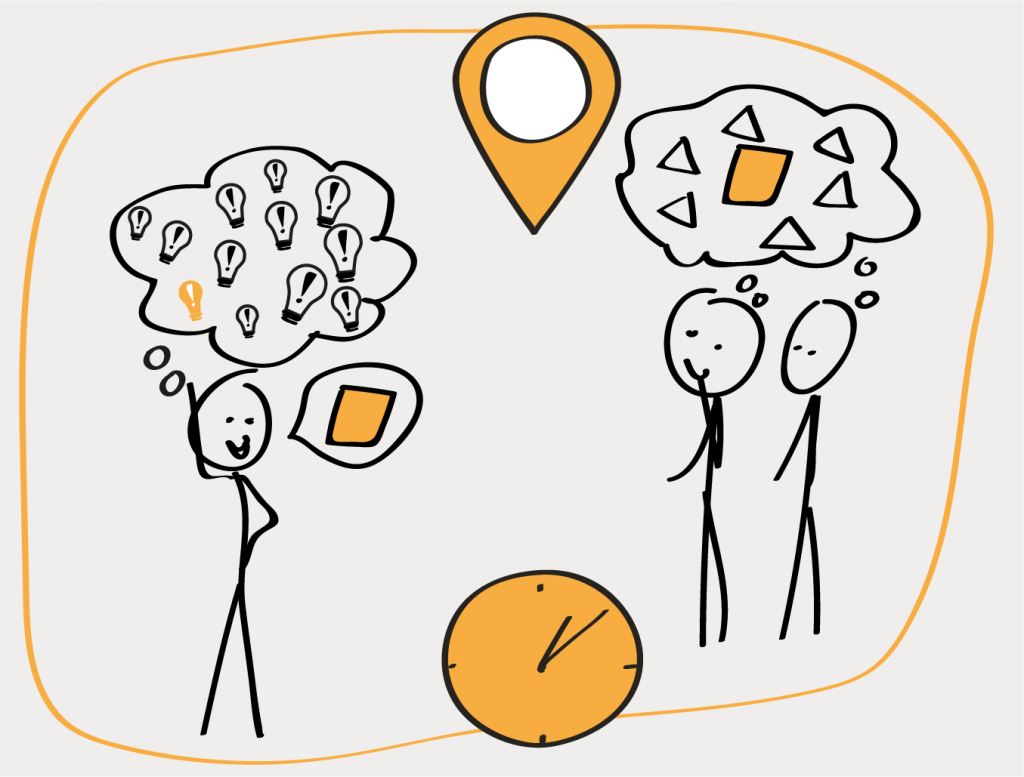

And if you are a person known for your creations, well you classify as a creative person. The focus of creativity research in this period was on the individual. What is it that these creative individuals are doing/thinking, what are their personalities, that makes them come to these ‘great’ results?

In this individual approach, creativity can be defined as:

‘a new mental combination that is expressed in the world’ (Sawyer, 2012: p7).

Nowadays, a more sociocultural approach is more popular to define creativity. Creativity can then be defined as:

‘the generation of a product that is judged to be novel and also to be appropriate, useful, or valuable by a suitably knowledgeable social group’ (Sawyer, 2012: p8).

Plucker et al. (2004) propose the following definition:

‘creativity is the interaction among aptitude, process, and environment by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is both novel and useful as defined within a social context.’

Runco & Jaeger (2012) propose a standard definition that says:

‘creativity requires both originality and effectiveness’.

These are only four definitions and we already have creativity defined as abilities, as a mental combination, as the activity of generating a product, as an interaction. And we have a standard definition that is no definition. Because saying that creativity requires originality and effectiveness is like saying lemonade requires water and lemons. But I want to find a definition that says lemonade is a drink that requires water and lemons.

As a result of these many definitions of creativity, we get conflicting research results. As Simonton (2018) put’s it: ‘if different assessments posit distinct underlying definitions, then contradictory empirical findings become almost inevitable’ (Simonton, 2018: p.80)

And here is a quote that says it all (Plucker et al. 2004: pp.88-89):

‘We do not define what we mean when we study “creativity”, which has resulted in a mythology of creativity that is shared by educators and researchers alike. In essence, all of these researchers may be discussing completely different topics or at least very different perspectives of creativity. This is not merely a case of comparing apples with oranges: We believe that this lack of focus is tantamount to comparing apples, oranges, onions, and asparagus and calling them all fruit. Even if you describe the onion very well, it is still not a fruit, and your description has little bearing on our efforts to describe the apple’.

In a forest of definitions on this level of psychology, I think it is a good idea to zoom out before I zoom in again.

What’s in a word

If we take a look at the word creativity we find the word create. To create is to bring forth into the new. That would be the very basic start of defining creativity.

To create is an action verb that used to be attributed to God or the Gods (CQ8 and CQ9). Since the Renaissance, we believe that people also have ‘creating powers’ (CQ9).

If to create is to bring forth into the new my first reaction is: how is ‘creating’ different from ‘making’? I think the answer lies in a word we see at many definitions on creativity: originality.

Originality to define created products

Imagine you worked in a screw factory in England in 1875 (the year creativity entered the English language). You stand behind a machine and you drill the crosses in the top of the screws. Now ask yourself: are you making screws or are you creating screws?

I go for making because there is no originality in making your 10.000th screw. The action of making the screw remains the same as well as the result. Of course, every new action is a new action and every screw is a new screw. But the similarity with the previous actions and the previous screws is high. And the similarity is not the friend of originality.

This example pinpoints the difficulty with originality. Runco (2014, pp.393-395.) describes this nicely. He argues on the one hand true originality in itself doesn’t exist because everything that is created is based on other creations. And on the other hand, you can argue that everything is original because every screw you make didn’t exist before and is new and therefore created. You know, ‘same same but different’. Go to Thailand or Vietnam if you don’t understand that phrase.

Originality to define creating: the creator vs that judger

What about the first screw you ever made? Would you have felt you created the first screw? I also would say no. In the screw-making machine, there is nothing from your own origin in it. You drill a hole in the top, that’s it. Of course, this is a personal issue.

I think for the maker originality has a different meaning than for the judger. The judger looks for similarity. The maker looks not only for similarity but also for him/herself (your origin) in the making process and in the result. This would mean that I could feel I have created while others might not view my making as a created product.

In the next paragraphs, I’ll focus on the judgment of the result of a created product, and not on the maker and his/her process of creation.

The addition of context for created products

If it is only originality that separates the created products from the made products we encounter a problem.

What about the first screw ever made? I would say the person who created the first screw (the inventor of the screw) was a genius and s/he definitely created the screw. It is all a matter of perception. When the screw was first invented it might have been considered a super original object. But now we think it is a normal everyday product.

Psychologists, therefore, argue we should judge the product in the time and space it was made in. That means when judging a product, the context should be considered.

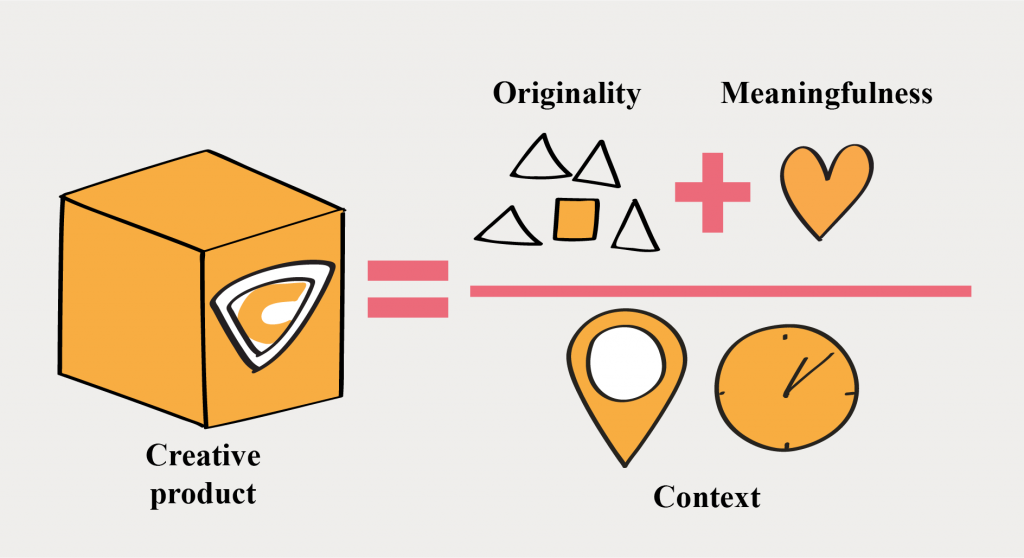

So far we have originality and context to define created products over made products (see figure below). But when do created products become creative products?

When created products become creative products

Take Picasso. The entire Western society regards Picasso’s paintings as creative. We think of his work as original in the context they were made in. So, he definitely created those paintings. Only the copies are ‘made in China’…

Now, take yourself. I think you can make a painting that could be judged as the original.

Maybe not as original as those of Picasso but still. Thus, you could create a painting. But, no offense, I’m pretty sure your painting wouldn’t be judged as a creative product (besides by your family maybe). Why is Picasso’s work judged as creative and your work not while you both have ‘made originality in context’ (read created paintings).

The answer lies in the quality of the work. Picasso’s work touches the heart, it is meaningful or has value for many others, your work doesn’t, sorry.

Now we get to the final part of a definition of creative products.

Defining creative products by originality and meaningfulness in context

We are zooming in again. Check out the socio-cultural definition at the beginning of the article and you will find some definitions that have two elements in them.

Originality is often part of definitions of creative output. Sometimes another word is used to describe originality. Novelty is a popular one (Plucker et al., 2004). Others are newness, unusual or unique (Simonton, 2018).

Effectiveness of the product is also referred to as usefulness in context, fit, appropriateness, utility, valuability, meaningfulness (Simonton). Usefulness in context is the most popular one (Plucker et al., 2004).

I like meaningfulness over useful and effective because I think meaningful encompasses all the other words. Why I like original over new or novel is more complex and I’ll get to that. In the figure below you find the equation of the creative product.

There are also psychologists that argue that the two elements of original/novel/new and useful/effective/meaningful are not enough. There are also those that separate some of these words into new words. For example, Boden (2004), defines creative products by novel, valuable and surprising. Sääksjärvi & Gonçalves (2018) define creative products by novelty, usefulness, and meaning. There are more options, see table one in Sääksjärvi & Gonçalves (2018) for an overview.

Scientifically it is an interesting discussion to determine the exact wording that defines a creative product. The big limitation of this discussion is that it is all verbal. In practice, the exact wording that defines a creative product is not super interesting.

Firstly, because all know it when we see it, we don’t need the words.

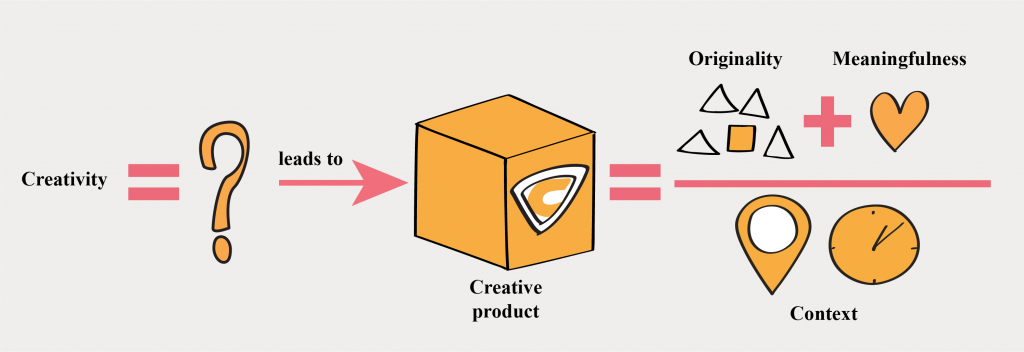

Secondly, and more importantly, creative output is on the right side of the equation. And we are interested in the left side of the equation. What is it that makes us create creative products? How can we increase the chance of a creative outcome? See the figure below.

Let me go back to your painting.

Your painting might not have been considered creative by others because it has no value for them, or it is not useful or whatever word you choose. However, your painting might have meaning for yourself. Not only because of the result but also because of the creating process. You might feel that you have poured your heart out in that painting or you learned a new technique. That brings us to the level of creativeness.

Level of creativeness of a creative product

I don’t think the level of creativeness is a phrase in psychology but I think it is a good summary of the 4c-model introduced by Kaufman & Beghetto (2009). I’ll be short on this.

Big-C creativity, the creative product was so original and effective (so creative), it changed the domain in which the creative product was placed. We give credit to eminent figures as I mentioned above to have created Big-C creative products.

Pro-C is for professionals. We are the experts, we create original and effective products but they do not transform the domain we work in. This is the destiny of most of us ‘knowledge workers’.

Little-c is often referred to as everyday creativity. It is what you and I do when we decide to change a standard recipe and find out that the food from our new recipe tastes even better than that of the original recipe. We judged our new product (the new recipe) as original and effective to us, and thus creative. (Although many of us wouldn’t call ourselves creative if we change a recipe).

Mini-c equals the learning process.

We want to learn from the Big-C guys to see how we can enhance the other c’s. And that brings us back to Guilford and all the other psychologists that study the individual side of creativity. What is it that makes these people created originality and meaningfulness? What is creativity? Great, I’ve written almost 2000 words and I still have the same question: what is creativity?

Conclusions: I miss the complete left side of the equation of creativity

At the beginning of this article, I sum up some definitions of creativity. To repeat myself we have creativity defined as abilities, as a mental combination, as the activity of generating a product, as an interaction between aptitudes, processes, and environment.

I like to see creativity as an activity of generating a product or idea. This activity happens in our bodies. (If we use quantum theory it could also happen between our bodies. I like that assumption.) Maybe we can control it for some part through mindset and skills. But also we could make a choice for a certain time or space in which we engage in the generative activity. And we can choose to some extent, the sequence of the action we take.

My questions would then be:

- What mindset and skills contribute to this generative activity (read creativity)?

- What environment supports creativity?

- What actions support creativity?

We will find in the next chapter some models that answer some of these questions And I will go full focus on actions in chapter 7, on mindset and skills in chapter 8 and on the environment in chapters 9 and 10. I hope that in week 52 I can finish the left side of the equation.

What’s next

What I completely left out of in this article is the difference between the creative output formulated as an idea or a product. The difference between idea and product might be the distinction between creativity and innovation. We’ll see next week.

You will find the cards for the next weeks below.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Boden, M. (2004). The creative mind: Myths & Mechanisms (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), pp. 444-454.

- Kaufman, J. C. & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), pp. 1-12.

- Plucker, J.A., Beghetto, R. A. & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why Isn’t Creativity More Important to Educational Psychologists? Potentials, Pitfalls, and Future Directions in Creativity Research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), pp. 83-96.

- Runco, M. A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice. Second edition. Oxford, UK: Academic Press.

- Runco, M. A. & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), pp. 92-96.

- Sääksjärvi M, & Gonçalves M (2018). Creativity and meaning: including meaning as a component of creative solutions. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 32, pp. 365–379.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Simonton, D. K. (2018). Defining Creativity: Don’t We Also Need to Define What Is Not Creative? Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(1), pp. 80-90.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ1: ‘Creativity is a lazy word’

Firstly, I wish you a happy, healthy and a h…[fill out your own h-word] 2020! Secondly, starting today I will post an article on creativity on my we

CQ22: Deliberate creativity methods

Can we be creative by choice? The word ‘deliberate’ implies we can. In this chapter I will describe four methods all based on the idea that we can be

CQ7: History is awesome!

If you would tell me twenty years ago that I would say that history is awesome, I would have kept you for a fool. I was born in the 80s and I grew up

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.