If you would tell me twenty years ago that I would say that history is awesome, I would have kept you for a fool. I was born in the 80s and I grew up in a society in which the sky is the limit and in which ‘the future is ours’. As a society, we are future-oriented. And not many of us were blessed with history teachers that could tell a good story. Most of us struggled to stay awake listening to all these boring years and events.

Why focus on History?

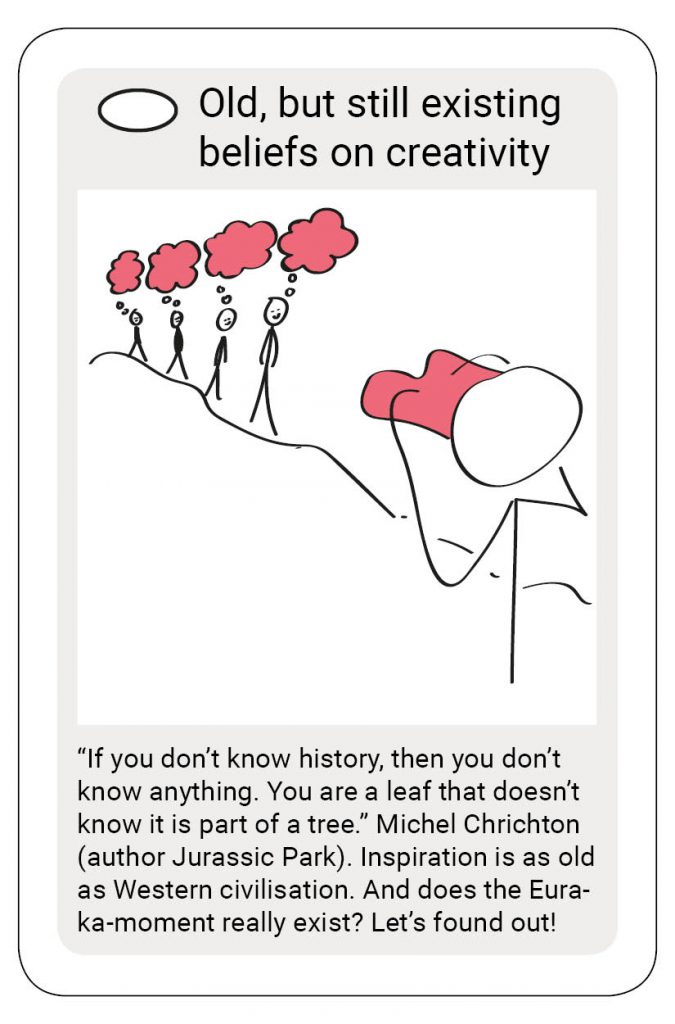

Our history is our memory. The present is a result of history and the future will be built on the present. Like Michel Chrichton, who we know as the author of Jurassic Parc, says:

“If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.”

Besides the importance, history holds amazing stories! Only look at the number of films that are based on ‘true events’!

In our daily work life, we move from project to project. We hate to stand still, look back and evaluate. While we all know the value of doing that. Of course, I am generalizing. You yourself are not part of this ‘we’, of course not.

What I was surprised about is that creativity researchers also rather look ahead than back. Which is weird in my opinion. How can you build a body of knowledge if you don’t know the body you are working on, if lucky only the pink or ear? I dived deeper into the historic consciousness of creativity researchers. This is important for us practitioners because it shows that we need to remain critical about anything we read on creativity: don’t assume, think! If you’re not interested, skip to the next part about the blocks in which I divide the history of creativity.

Creativity researchers lack a historical consciousness

There, I’ve said it.

With the 20 year existence of The Creativity Research Journal chief editor, Mark Runco wrote an article called ‘Correcting the Research on Creativity’. He found that through the years, new research articles on creativity poorly cite other authors. He gives two potentials reasons for this. One, citations have become superficial because only online available citations are used (Runco, 2007). Most authors probably do this unintentionally. And two, there is an originality bias when it comes to creativity research. Because originality is highly valued in creativity, creativity researchers could easily be seduced to make their research seem more original than it might be, it is all about the citation choices the authors make. The consequence is as follows:

‘Sadly, they may be reinventing the wheel. Even if not a reinvention, this kind of work does not contribute to the advance of creative studies, because it does not integrate the findings and ideas with the rich literature which already exists.’ (Runco, 2007: p. 322)

Runco (2007) gives examples of this ‘reinventing the wheel’ for topics like intrinsic motivation, domain specificity, and paradoxical persons. To solve a part of this problem the Creativity Research Journal has a new part called ‘corrections and comments’. The idea is that this section points readers and authors to earlier work that should or could be considered in the context of the given argumentation.

Runco (2007) ends with the conclusion that it is still good to visit a library (‘even if it doesn’t have a Starbucks’) and that literature reviews would be helpful, especially the ones that take long views that include older as well as newer research.

In an e-mail (28/8/2019) Runco told me:

‘I am often disappointed that more credit is not given to early important figures. Science is cumulative and yet many people forget it–or intentionally ignore citing earlier work.’

Recently, Glaveanu (2019) edited a book in which contemporary creativity researchers reviewed some influential work from other researchers that worked between 1850-1950. Most interestingly, the original texts of those works were included in the chapters. In the preface of this work, he argues for the necessity of this book. He even states that there is a myth amongst creativity researchers that creativity research started with the keynote speech Guilford made in 1949 to the American Psychology Association (APA)! In that speech, he stated creativity as a legitimate topic to research within the field of psychology. And that scholarship randomly chooses to look only five years back (Glaveanu, 2019).

In line with Runco (2007), Glaveanu told me (email 28/8/2019):

‘By forgetting the long history of our field we are condemned to repeating the same conceptual mistakes that make the field of creativity research both very diverse but also very fragmented today.’

For research this is bad, but also for us practitioners this is bad. Because it doesn’t help us at all to understand why what we are doing works! We keep running in circles. That having said, let us focus on we do know on the history of creativity.

Mapping historical beliefs in four cards

Since I am creating a quartet and I have one chapter dedicated to the historical beliefs on creativity, I need to scrap some stuff. Firstly, there are beliefs or theories from the past that will return in other chapters, so I won’t take those into account here, you will find out later what these are. Secondly, I look into theory on creativity. I find that history on the theory over creativity can be divided into four periods, described below. That sounds good, four periods, four cards. However, these periods are ‘something to keep in mind’ but don’t give us the four beliefs we can write four articles about. So, I will flip it around. I will take focus on the beliefs that were born long ago and in which we still believe today. I will give you the four periods to keep in mind and then the beliefs that I will focus on in the next four weeks.

The four periods to keep in mind

History of Creation

Almost every scientific article on creativity starts with the definition problem: ‘What is creativity?’. According to Weiner (2000), if we take the broadest term of creativity: ‘bringing something into the new’, we could argue that the history of human progress is in fact history of creativity. And some very fundamental ideas of Western society were born in Ancient Greece and Israel.

If we want to create a complete overview of creativity research we should start way before the birth of Jesus Christ. Basically, we should start at the beginning of life. Good luck with that.

History of Scientific Research

When discussing research in a scientific way, our history starts somewhere during the Renaissance and takes shape during the Enlightenment (Weiner, 2000; Runco & Albert, 2010). Like any type of scientific research that is not physical, creativity research is very much influenced by people that generally contributed significantly to the act of doing scientific research on non-physical matters. Therefore a big chunk of the literature of the History of Creativity Research is basically literature of how Western scientific research came into existence in general.

History of Science on Human Behavior

Then, around 1800 more scientific disciplines around Human Behavior take shape, starting with Adam Smith but also Darwin was a huge influencer when it comes to inspiring creativity researchers (Runco & Albert, 2010). It can be argued that around this period laid the specific foundations for creativity research. (Becker, 1995; Glaveanu, ed. 2019).

History of Creativity Research as such

Then, there was Guilford giving his presidential speech in 1949 for the American Psychology Association (Guilford, 1950). (The speech was in 1949, the publication of the speech in 1950.) Himself leading the way in modern psychological creativity research.

With those four periods in mind, we move through history in a different way. And we see what beliefs on creativity we find that we are still believing today.

Old, but still existing beliefs on creativity

Inspiration as gift from the Gods

I mentioned at the introduction of the quartet that I would only focus on Western beliefs on creativity. So I will start with the beginning of ‘The West’. Of course, that beginning is also debatable. I’m starting in Ancient Greece with Plato and Aristotle. We will find that the idea of inspiration is 2600 years old! And association theory, 2500 years old! The connection of creativity with drugs was also born this period.

Creativity as a human ability

Then we move quickly through the Dark Ages, in which ‘nothing happened’ and we continue our story in the Renaissance. Of course, an era of creation but also important for our beliefs on creativity. The recognition of the human ability to create became a thing in this period. And it is the period of Mister Creativity himself: Leonardo Da Vinci. Read his biography!

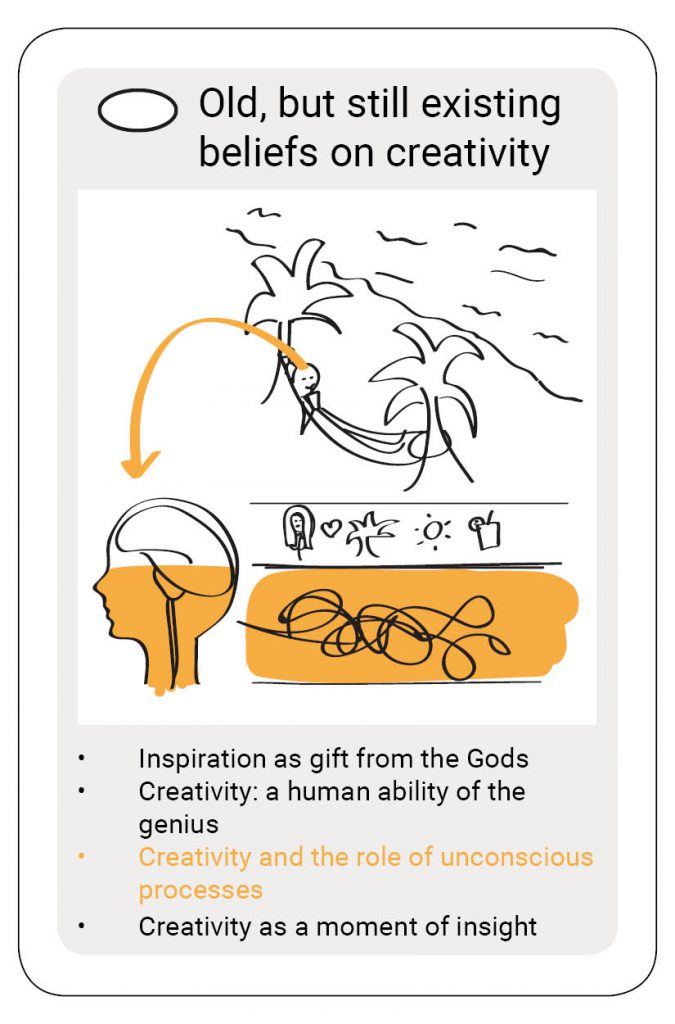

Creativity to express emotions

Again we accelerate through the period of Enlightenment and go to the Romantic Period. Creativity became a quality for artists through which they could express their emotions. And the ‘divine madness’ from the Ancient Greeks became insanity of the crazy creators.

Creativity as a moment of insight

This chapter will stop in the Industrial Revolution in Germany, with the Gestalt theory on problem-solving. A theory that is not so popular anymore in the world of science, but very popular ideas from the Gestalt theory also returns in Design Thinking.

Here are the cards for the next four weeks:

Thanks for reading and I wish you a pleasant continuation of your day.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Becker, M. (1995). Nineteenth-century foundations of creativity research. Creativity Research Journal 8(3), 219-229.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (ed.) (2019). The Creativity Reader. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Runco, M. A. (2007). Correcting the Research on Creativity. Creativity Research Journal 19(4), 321–327

- Runco, M.A., and Albert, R. S. (2010). Creativity Research: A Historical View. In Kaufman J. C., and Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, pp. 3-19. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Weiner, R. P. (2000). Creativity & beyond: Cultures, values, and change. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

If you would tell me twenty years ago that I would say that history is awesome, I would have kept you for a fool. I was born in the 80s and I grew up in a society in which the sky is the limit and in which ‘the future is ours’. As a society, we are future-oriented. And not many of us were blessed with history teachers that could tell a good story. Most of us struggled to stay awake listening to all these boring years and events.

If you would tell me twenty years ago that I would say that history is awesome, I would have kept you for a fool. I was born in the 80s and I grew up in a society in which the sky is the limit and in which ‘the future is ours’. As a society, we are future-oriented. And not many of us were blessed with history teachers that could tell a good story. Most of us struggled to stay awake listening to all these boring years and events.