CQ12: Theory vs. Practice: Finding your way through theory as creativity practitioner

The problem occurs when you are a practitioner like us. It is our job to get other people more creative. It would be nice to understand how creative processes work. That way, we can create smart interventions to enhance creativity.

The problem occurs when you are a practitioner like us. It is our job to get other people more creative. It would be nice to understand how creative processes work. That way, we can create smart interventions to enhance creativity.

It is my assumption that if we understand the theories and main assumptions behind the methods we use to enhance creativity, we will become better at it.

But when you have multiple scientific disciplines that carry out research on creativity using different definitions on creativity (CQ14), researching different aspects of creativity (creative person, product, product, place) and using thirty different research methods (Clapham, 2011), it is kinda difficult to draw good conclusions.

For example, let’s say we want to know how we can get participants creative during a workshop. A neuroscientist using definition 1 and research method 2 concludes that working in silence leads to more creativity. A social psychologist using definition 3 and research method 4 concludes that conversing with others leads to more creativity. Now what?

In the previous two chapters, I focused on how we as a society think about creativity and I showed that some strong beliefs we hold on creativity are pretty old. This type of knowledge gives us more context in understanding creativity.

In this chapter, I will tackle four creativity related topics that have been extensively discussed in science. See ‘what’s next’ at the end of this article for an overview of these topics. Of course, there are more than four topics extensively discussed in science. For this Creativity Quarte,t 2020 I chose the topics I think are most relevant for our work as practitioners.

By the end of this chapter, we should be able to understand how to deal with the claims from the neuroscientist and the social psychologist I gave in the example above.

Science-says claims

Let’s continue with this example of the neuroscientist and the social psychologist. As a practitioner, I could write a blog on a technique I use to get participants more creative. Important in this technique is that participants work in silence. To showcase that people become more creative when they work in silence, I search online if I can find a scientific article to support my claim. And voila! I found an article that refers to the scientific research of the neuroscientist. Thus I write: ‘Research (the neuroscientists) says people are more creative when they work in silence’.

Of course the same goes if I blog about a technique that requires participants to talk out loud. Online I find a reference to the scientific article of the social psychologist. And thus I write the opposite of what I found from the neuroscientist: ‘Research (the social psychologist) says people are more creative when the work out loud.’

The problem is the lack of context. What if the conclusions the neuroscientist drew are ‘true’ in situation A and the conclusions the social psychologist drew are ‘true’ in situation B. We need to know the boundaries of these conclusions before we can make sense from them. If we read these science-says claims as I described above we know nothing. Without context, we know nothing (you know nothing Jon Snow, for the Game of Throne fans).

What can we do about this as readers and as writers?

5 ways do to a science-says check

Understanding the context of a science-says claim is difficult when you don’t have access to the article yourself. For most practitioners, scientific articles are hidden behind a thick icy wall (to remain the Game of Thrones metaphor).

It sucks, I know. It would be great if all science paid by taxes should be available for the people that paid the taxes. This is a complex matter, different stakes involved, etc. I don’t want to get into that here. Even if this is the case you do have options. Here are five actions you can take to help you judge a science-says claim.

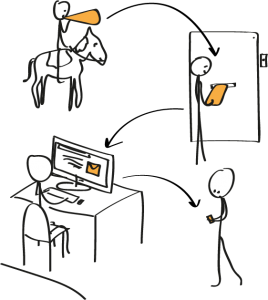

1: Open source science websites

The world of science is changing and more and more theory becomes openly available, woohoo! Research Gate offers a wide range of scientific articles. In the Netherlands, we have ScienceFinder where you can type in your topic and find out where and who does research on your topic. It also shows openly available scientific sources. You can use these sources as a reader and as a writer.

2: Google books

Many older (but still influential) books are available on Google Books. If the book is not available as a whole, you can always search for keywords. Google will show the pieces of pages that contain these keywords. This is a puzzle, reading half pages, but you can gain knowledge from it, in my experience at least.

Moreover, if you use a science-says claim yourself, and it comes from a book, please mention the pages as well, so the readers can look it up and make up their own minds.

3: Check the summary

There is much we can learn from only a summary of an article. Here is how to find summaries and what to look at.

First, find the summary. Well, I assume we all use some sort of referencing when we make a science-says claim in our blogs. This is your starting point as a reader. You probably have the name of the author or the university or a link to a website.

Second, you can use Google Scholar, ScienceDirect or Scopus to find the article behind the reference if the first reference doesn’t lead to the article itself.

Third, when you found the real source you can search online for a summary. Summaries are always available.

In these summaries, you need to look for two things.

First, a summary will give you the context in which the conclusions were drawn. In other words, a little piece of context is openly available.

Second, you can estimate the extrapolation possibilities of the article by understanding the type of research the article presents. Let me explain that.

Generally, you will recognize four types of articles*; empirical research articles, meta-analysis articles, descriptive articles, and review articles. The first ones are super-specific and the last ones are more general. Thus there is more risk generalizing a science-says claim from an empirical research article than from a review article.

*If you are a researcher and know I’m wrong here, please correct me. I’ll change the article.

I’ll give a short description of all four and specify which ones are preferable to use.

Empirical research articles

Empirical research articles are the majority of the articles you will find. Empirical research is about making observations and drawing conclusions from those observations. This type of research is how we ‘practice science’. The foundation was laid by Bacon in 1620 (his book is openly available online, here, also see CQ9). Through this type of research, many disciplines build on a body of knowledge on specific topics.

Like I said, empirical research articles don’t give us practitioners a lot of information. Empirical research is ‘niche’ work. What is true in situation A might be different in situation B. Scientists know this, that is why each article has a reliability, and a validity section.

Thus, if you read a science-says claim referring to an empirical research article, be superstitious if the blogger simply accepted the conclusions as generally true.

If you use an empirical research article to support your claim, please mention the context or leave a link to the summary of the article. So we can find the scope for which this claim is ‘true’ ourselves.

Descriptive articles

I’m pretty sure this is not a word researchers would use. With descriptive articles, I mean articles that don’t use statistics but argumentation to make a claim. Articles I used for CQ3 on the societal understanding of creativity I used descriptive articles. They often come from other disciplines than psychology, like anthropology or cultural history.

Since they are generally more context-driven, I would say give us more general conclusions. (Please correct me if I’m wrong here.) And thus I think these articles give us more information that empirical research articles. Again, I’m not an expert in this type of research, I’m leaving it up to you to make up your own mind…

Meta-analysis articles

Meta-analysis articles describe research on research. The researchers use data from multiple other studies and make new calculations with this bigger data set. In these articles, we’ll find conclusions not based on a few, but on many, experiments. Therefore, meta-analysis articles should be more reliable than empirical research articles.

In my opinion meta-analysis articles are good sources.

Review articles

In review articles, the author looks into back in time and gives us an overview of what is research so far, and what we could conclude from that. I think these articles draw the most general conclusions. I like to use these myself.

Yes, we can gain all this information from a summary, and sometimes even from a title alone! Moving on to point four.

4: Check the author’s credentials

Search for the author of an article online. You can check how often s/he is cited (doesn’t say everything, but is says something). Often these people have profile pages on their university websites. This will also give you some insight into the author’s expertise and therewith reliability of the source.

5: Use your network

Before my part-time job at the Delft University of Technology, I used to e-mail friends who have university accounts to get me a specific article. I still do that for articles I cannot reach from my Delft-account. If you are in a desperate search for a particular article, let me know, maybe I can look it up for you :).

My general point: be critical

Look, I understand, we are practitioners, not theorists. There is a reason we chose a profession that doesn’t include these reading scientific articles.

However, if we read a science-says claim, and especially if we make one yourself, we have no choice. At least not in my opinion. I think as professionals, we should remain critical. I hope these five tips on how to find your way through science will make this part of your job easier.

Moving on to the cards of the third chapter of the quartet.

What’s next

I promised a short description of the cards and articles that are part of chapter three of my Creativity Quartet 2020. Here they come.

Domain-specific vs. general ability

Is creativity a domain-specific ability or a general ability? There has been quite some debate among scholars about this issue. The question is whether the process of creation of a chef cook differs from the process of creation of a scientist or a poetry writer. The role of expertise plays a role in this discussion. I can already say that it appears as if there is no true consensus on this issue yet. Appears at least…

Definition debates on creativity

I can’t postpone it any longer, I have to get into the definition discussion. I already gave some definitions in the previous two chapters. In this article, I will elaborate on the different definitions researchers work with.

After reading this article you will be better at pinpointing what type of definition you are using yourself. And you’ll be better at recognizing hidden assumptions on creativity by others. This will help us to overcome miscommunication. Furthermore, I’ll try to elaborate on the implications in the practice of choosing a certain definition of creativity.

Creativity vs. Innovation

There is a whole body of knowledge on innovation that does not return in the body of knowledge on creativity, and vice versa. The most common understanding of the relationship between creativity and innovation is that creativity is the cause and innovation is the consequence. That is unsatisfying to me and I think too simple. Understanding this relationship is important for our work because a lot of workshops that involve creativity have the goal of innovation.

Does creative thinking even exist?

I will close this chapter with a nice topic. We all assume there is something called creative thinking. Guilford (1950) made this a popular idea. And there is all this theory on creative thinking and there are many types of training that involve boosting your creative thinking skills. However, we have to ask ourselves if there even such a thing as creative thinking? I love this question, it challenges everything. It’s not a popular question though. If creative thinking does not exist, do we still have a job?

You will find the cards for the next weeks below.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), pp. 444-454.

- Clapham, M. M. (2011). Testing/Measurement/Assessment. Encyclopedia of Creativity: Second Edition, eds. Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R., London, UK: Academic Press, 2011, Vol 2. pp. 458 – 464.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ23: Creative Problem Solving, the ins and outs

As the term implies, CPS is a method to train people on how to enhance their creativity and become more ‘creative’ problems-solver. I am positive that

CQ8: Divine inspiration

Inspiration is a Gift from the Gods. Right. Let’s start our historical review with the Big 3: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. I will shortly mention t

CQ15: What is the difference between creativity and innovation?

I recently became the new President of the European Association of Creativity & Innovation (EACI)*. From that perspective, it would be nice to cla

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.